I have recently

been reading of and writing on many African issues. One thing that strikes me

quite strongly is the depth to which false perceptions of Africa have sunk in

our collective subconscious. While I think it is forgivable for people whose

only experience of Africa is aid adverts with awfully malnourished children and

news bulletins featuring some rabid warlord spouting maledictions – this

delusion of utter dependence should not be replicated by Africans. This is why

we have autobiographies and biographies. The person describing herself has

greater insight than the person retelling the tale. A self-portrait is not a

caricature. We Africans have flipped the script. We have reproduced the

caricature in our understanding of ourselves, in telling our stories and

understanding the heart of Africa. We have replaced the cradle of life with a

heart of darkness. So I have a 5 step solution. We need to begin thinking and

fast.

What is Africa? Take a step back from

all that has been said, especially by the media. Read the works of Africans.

Look at the Africa around you. Africa is not the few unscrupulous leaders we

have, Africa is its people. So look at its people. Africa is an eternal thought

in the mind of God. There was always Africa. Ignore the countries/states. While

I am not in favour of the breakup of states, we must remember that

nation-states are made, not imagined. The states in Africa were imagined by

people who never set foot on our tropical shores. Obama once said ‘The worst

thing that colonialism did was to cloud our view of our past.’ We need to claim

our identity as African and divorce this quest from a political one. We have bought into thinking we can truly be

what we should be by ensuring our ‘brothers’ place in political office. How’s

that working for you thus far? Go and explore, and think what it means to be Africa.

Africa was before Nigeria.

Colonisation and the sense of inferiority:

Now I really do hate to bang on about colonialism. However, let us say as an

analogy, someone scratched you with a sharp nail. Then went away. The scratch

becomes septic because the wound is not cleaned, because the damage is not

understood. Do we say the scratch is in the past and fail to treat the wound?

By no means! We may forgo pursuit of the culprit. We may refrain from a lengthy

and arduous litigation, but we do not deny existence of the wound. Make no

mistake colonialism is a wound on the psyche and insult to the soul, a

generational offense that lingers unacknowledged on the edges of our

subconscious.

Thomas Pynchon,

said, ‘Colonies are the outhouses of the European soul, where a fellow can let

his pants down and relax, enjoy the smell of his own shit.’ (Imagine!)

Our Africa was

the Petri dish in which the experiment of empire was conducted. And when the

experiment failed, the apparatus of psychological oppression hangs on in our

minds like a never-fading apparition. How did a handful of administrators

manage to shackle the African giant? By imprisoning the most important part of

a people – their sense of self-worth. By making us believe that we were

inferior, that our laws, customs ideas were of no value, thus our minds were

captured into the colonial Black Maria and our bodies soon followed. We see

vestiges of this in everyday discussions and actions: Parents failing to teach

their children African languages, people using ‘that’s what they do in London’

as a trump card in arguments, skin bleaching, naming of children, the

repugnancy principle, acceptance of non-African standards of beauty……. The list

could go on for years.

Patrice Lumumba

of Congo is famed to have said to the departing Belgian colonists ‘Nous ne

somme plus vos singes [or macaques].’ ("We are no longer your monkeys).

The truth is more complex as words are cheap. Attitudes need to change.

Self-knowledge: The first step to

changing attitudes is self-knowledge. Africans, I believe have a problem with

self-awareness and self-knowledge, especially as concerns the nature of that

self- knowledge. Arundhati Roy talks about the psychology of globalization

thus: ‘It's like the psychology of a battered woman being faced with her

husband again and being asked to trust him again. That's what is happening. We

are being asked by the countries that invented nuclear weapons and chemical

weapons and apartheid and modern slavery and racism - countries that have

perfected the gentle art of genocide, that colonized other people for centuries

- to trust them when they say that they believe in a level playing field and

the equitable distribution of resources and in a better world. It seems comical

that we should even consider that they really mean what they say.”’

The problem with

Africa is that we still trust foreign ideas more than our own. We take these

false narratives, these illusions of altruism and we internalise them and make

them our own. In the quest for a better world, we intuitively understand our

world to be worse. We make no allowance for our intersectionality. We are

black, generationally oppressed, women, men, children, poor, third world… yet

we do not speak of how these factors affect us personally. No one else can see

our pain. This pain is ours, but we swallow it, we stomach it, and let it

fester deep within us like fermenting cassava, its poisonous cyanide, killing

us from the inside. Spit it out!

Ask a hundred

non-Africans to describe Africa, there responses would be fairly similar. Ask

the same of a hundred Africans… Self knowledge unlocks the heart of Africa.

Africa defies definition, but that is no excuse not to think of her.

‘Africa is

mystic; it is wild; it is a sweltering inferno; it is a photographer's

paradise, a hunter's Valhalla, an escapist's Utopia. It is what you will, and

it withstands all interpretations. It is the last vestige of a dead world or

the cradle of a shiny new one. To a lot of people, as to myself, it is just

“home.”’ Beryl Markham

Africa is home,

I am Africa…

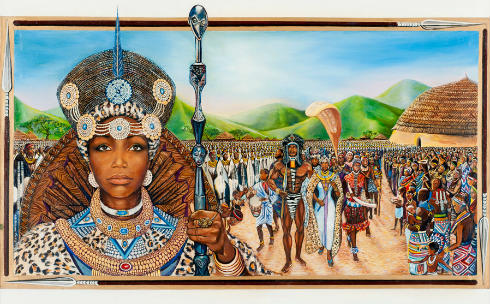

Historical and Contemporary knowledge:

There are very few things that upset me and annoy me as much as an African

spouting inaccurate and derogatory ‘facts’ about Africa. A multiple degree

holder once told me, ‘no African entity had ever succeeded.’ I had to

physically restrain myself, or else we would have needed industrial cleaners to

clean the blood from the walls. Did he not know of the Ghana Kingdom with its

riches in gold that existed for 1000 years? Or the Oyo Empire that traded far

and wide? Or the Buganda and Bunyoro kingdoms of present day Uganda? Or the

supposition that Africans do not know about leadership… All I have to say to

that is… Mai Idris Alooma, Nana of Itsekiri, Askia Mohammed (Askia the Great), Sonni

Ali, Shaka Zulu (kaSenzangakhona), Mansa Kankan Musa, Sundiata Keita, Alaafin

Oranyan, Cetshwayo kaMpande, Ahosu Ghezo, Asantehene Opoku Ware and ASANTEHENE OSEI

TUTU AGYEMAN PREMPEH II!!

And African

women? Oya come and read this:

Cleopatra, Moremi

Ajasoro, Iyeki Emotan Uwaraye, Efunsetan Aniwura, Queen Amina, Inikpi of

Igalaland, Taytu Betul, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, Queen Nzinga, Omu Okwei of

Osomari (Felicia Ifeoma Ekejiuba), Aba women’s Riot, Lagos Market women’s riot

and the Dahomey Mino (a Fon all-female military regiment).

If you don’t

know who these people are or what I am talking about, shame on all the

education systems in the world. Our history is a fact that happened no matter

what you have heard, I dare you to act like it.

Answer me these

questions:

Who discovered

the River Niger?

Who was the

first man in South Africa?

We need to be aware that schools

set up by the colonial powers were primarily set up to enable communication

between the coloniser and the colonised. In that sense they were mainly centres

of instruction. However, they have gradually become educational institutions,

though educational content in many African curricular still retains vestiges of

post-coloniality. This the point of the questions I asked above.

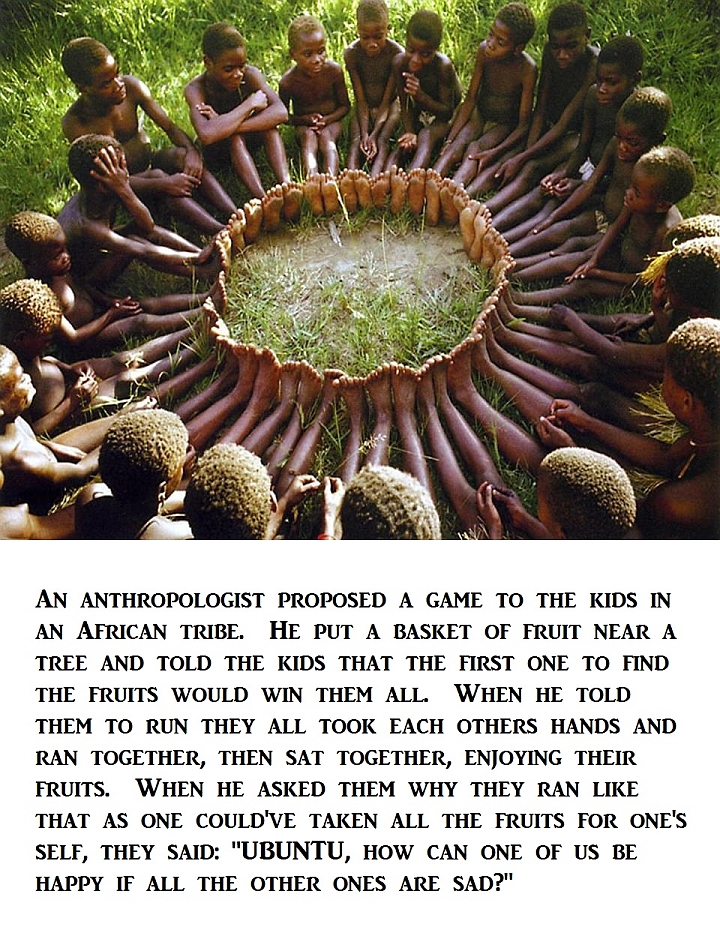

On the other hand, African

indigenous education emphasises training individuals to contribute to the

development of their community and the benefits of a cohesive communal life.

Conversely colonial education emphasised the value of the individual and

deemphasised the importance of community and culture. Where education seems to

isolate the individual from her community, education and its proponents become

a communal enemy. These incongruences as well as the colonial purposes of

education result in an irrelevant curricular – Shakespeare taught without

context – inherited inadequate teaching methods, and disengaged cohorts of

students.

Why do we learn Shakespeare?

Or why is cramming an integral part of our education?

Education is not entirely beneficial

if it becomes a means by which a person’s identity, culture and language

becomes obscured. Education is meant for the FULL development of the human

person – the mind, the body, the heart and the soul. Nelson Mandela once said ‘If

you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you

talk to him in his language… that goes to his heart.’

We fail to learn

our own languages, sing our own songs, dances to our own rhythms, to the beat

of our hearts, to the steady thrum of our soul. The problem is that we approach

knowing from an externalised perspective. We see knowledge as something outside

of us that we have to assimilate. But it is not. We need to read more, [aim to

read a book a week – any book will do], to be more self-aware, then connect what

we have learnt with who we are, for the full development of the African

personality that lies inside of us.

As Robert Nesta

"Bob" Marley sang

‘Emancipate

yourselves from mental slavery;

None but

ourselves can free our minds.’

Word!

Self-esteem: The first black African

woman to win a Nobel Prize, Wangari Mathaai said ‘our people have been

persuaded to believe that because they are poor, they lack not only capital,

but also knowledge and skills to address their challenges. Instead they are

conditioned to believe that solutions to their problems must come from

‘outside.’’’

We can only shed

this innate belief when we accept the validity and worth of our existence. What

the colonised African mind suffers from is a severe case of post-colonial internalised

oppression. Even when the primary source of the oppression no longer exists, we

oppress ourselves with our own feelings of inferiority. We think anything from

‘oversea’ will be better than ‘tiwantiwa’

just by the fact of their different sources. Aba shoemaker will make fine shoe

and stamp Italy on it. As some status-conscious person once told me, even her

dead body would refuse to wear lace that wasn’t Swiss or other European origin,

to the extent that we import traditional attire. I am sure many Nigerians will

refuse to enter a car that is made in Nigeria.

On a more

psychological level and especially in the diaspora, we see many people exhibit

shame and refuse to identify as African. To this end they twist their tongues

into unimaginable shapes to produces sounds completely unintelligible, in

attempt to adopt an accent foreign to them. We call our languages vernacular, yet

these are languages of a living people, not a jargon to be hidden from the sun.

The focus on English, French

and Portuguese as languages of instruction and national communication has also

contributed to the disappearance of African languages and customs. Prof E. E. Adegbija

notes ‘Over 90% of African

languages,…exist as if they don’t really exist; they live without being really

alive. Living functional blood is being sucked out of them…’

So we live a half-life as

Africans, other people tell us what should matter to us. The West tells us we

should resist our ethnicities and cultures, our governments and their

corruption. Our governments tell us that the West is our enemy, and that our

next door neighbour is our enemy and ‘see, I built this road!’ Did they build

it with their own money?

These are the symptoms of self-oppression, not being

able to refute the fallacies around, because we fear the dark recesses of our

own minds and fear lurking in the corners of our consciousness. If we dare to,

quietly and stoutly, consider all around us, take those books off of the

shelves and learn of truth that is not really hidden, we may learn one

certainty. Our minds are being held captive by our own thoughts, that captivity

imprisons us into a life less than we were made for.

How did a handful of administrators manage to shackle the African giant? By imprisoning the most important part of a people – their sense of self-worth. By making us believe that we were inferior, that our laws, customs ideas were of no value.

How will we unshackle the African giant? By freeing our minds from mental slavery, by realizing that we are worth as much as anyone else, by eschewing narratives based on inferiority, by connecting once again with the Africa that lies inside of us - The true Africa whose heart is golden.

How did a handful of administrators manage to shackle the African giant? By imprisoning the most important part of a people – their sense of self-worth. By making us believe that we were inferior, that our laws, customs ideas were of no value.

How will we unshackle the African giant? By freeing our minds from mental slavery, by realizing that we are worth as much as anyone else, by eschewing narratives based on inferiority, by connecting once again with the Africa that lies inside of us - The true Africa whose heart is golden.

No comments:

Post a Comment